Lizards exhibit a diverse range of anatomical and physiological traits that have evolved to suit their various ecological niches. These adaptations include unique sensory organs, thermoregulation behaviors, and reproductive strategies.

Call Us when you Need Help!

Lizards

Lizards are a diverse group of reptiles belonging to the order Squamata, which includes over 7,000 species classified within the suborder Lacertilia. Found across a wide range of habitats on every continent except Antarctica, lizards play significant roles in various ecosystems as both predators and prey. Their remarkable adaptability and evolutionary history have made them subjects of extensive scientific study, contributing to our understanding of biodiversity, ecology, and conservation. Notable for their varied anatomical and physiological traits, lizards exhibit adaptations that enhance their survival, including specialized sensory organs, thermoregulation behaviors, and unique reproductive strategies. Their classification is complex, encompassing numerous families and genera, each displaying distinct morphological characteristics. For instance, the monitor lizards of the family Varanidae are known for their size and predatory skills, while geckos of the family Gekkonidae are recognized for their ability to climb and adhere to surfaces through specialized toe pads.

Lizards are also facing significant threats from habitat loss, climate change, pollution, and illegal wildlife trade, with approximately 20% of species classified as threatened or endangered.Conservation efforts are increasingly crucial to protect these reptiles, highlighting the need for habitat preservation, sustainable practices, and community engagement in conservation initiatives. The cultural significance of lizards further underscores their importance; they appear in various mythologies and modern pop culture, symbolizing resilience, wisdom, and adaptability, thereby enriching human narratives and ecological interactions.In summary, the study of lizards encompasses a wide array of topics including their classification, anatomy, behavior, conservation status, and cultural significance, making them an integral part of both ecological systems and human culture. Their unique adaptations and ongoing challenges highlight the importance of continued research and conservation efforts to ensure their survival in a rapidly changing world

Classification

Taxonomic Hierarchy

Lizards are classified within the order Squamata, which encompasses a vast diversity of reptiles, including snakes and amphisbaenians. The scientific classification of lizards falls under the suborder Lacertilia (or Sauria) and is further divided into various infraorders and families, which categorize them based on morphological, genetic, and ecological traits. With over 7,000 species recognized globally, the classification of lizards reflects their extensive evolutionary history and adaptation to various habitats.

Lizards are grouped into several infraorders and families, which are as follows:

- Infraorder: Iguania

- Family: Iguanidae (iguanas and spinytail iguanas)

- Family: Agamidae (agamid lizards)

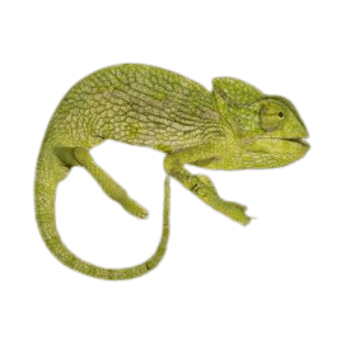

- Family: Chamaeleonidae (chameleons)

- Infraorder: Gekkota

- Family: Gekkonidae (geckos)

- Family: Pygopodidae (legless geckos)

- Family: Phyllodactylidae (leaf-toed geckos)

- Infraorder: Scincomorpha

- Family: Scincidae (skinks)

- Family: Lacertidae (true lizards)

- Family: Teiidae (whiptails and tegus)

- Infraorder: Anguimorpha

- Family: Anguidae (glass lizards and slowworms)

- Family: Helodermatidae (Gila monsters and beaded lizards)

- Family: Varanidae (monitor lizards)

- Infraorder: Amphisbaenia

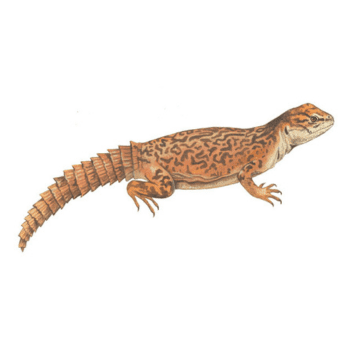

- Family: Amphisbaenidae (worm lizards) Each family contains numerous genera and species that exhibit unique characteristics and adaptations suited to their environments. For example, the Family Scincidae includes skinks known for their smooth, shiny scales and elongated bodies, while the Family Varanidae comprises large monitor lizards that are adept predators.

Phylogenetic Relationships

The classification of lizards is not only based on observable traits but also incorporates genetic data that elucidate their evolutionary relationships. Historically, classifications have varied, with some grouping based on morphological features while others emphasize molecular phylogenetics. For instance, studies have shown that certain families, such as Iguanidae, are closely related to collared lizards (Crotaphytidae), suggesting shared ancestry

. Current classification schemes propose a monophyletic grouping for several families, indicating that they all share a common ancestor. This evolutionary perspective aids in understanding the intricate relationships within the reptilian world and the adaptive radiations that have resulted in the diverse forms of lizards we observe today

Convergence and Diversity

Lizard classification also reflects instances of convergent evolution, where unrelated species develop similar traits in response to comparable environmental challenges. This phenomenon underscores the complexity of lizard diversity, as certain traits may arise independently in different lineages. For example, adaptations for climbing can be found in both chameleons and some gecko species, even though they belong to distinct families.

Specific Habitats by Species

Iguanidae (iguanas and spinytail iguanas)

Large herbivorous lizards with dewlaps and dorsal spines. Excellent thermoregulators found in tropical Americas. Green iguanas can reach 6 feet length, important in ecosystems.

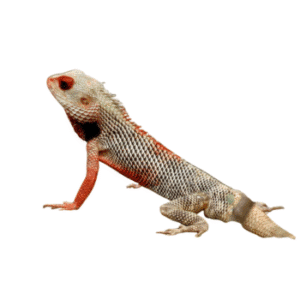

Agamidae (agamid lizards)

Old World lizards with acrodont teeth. Diverse family including bearded dragons, frilled lizards. Display elaborate territorial behaviors, color changes, and specialized head ornamentation.

Chamaeleonidae (chameleons)

Distinctive lizards with independently moving eyes, projectile tongues, and prehensile tails. Zygodactylous feet for climbing. Approximately 200 species, mostly African, with remarkable camouflage abilities.

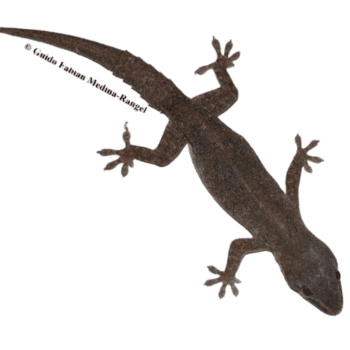

Gecko (Hemidactylus frenatus)

Small pale gecko with sticky toe pads. Active at night, produces clicking sounds, leaves droppings on walls and surfaces Common Types of Wood-Boring Beetles | Hawx Pest Control. Most widespread indoor pest lizard across India.

Gecko (Hemidactylus brookii)

Similar to common house gecko but smaller. Frequently found in bathrooms, kitchens, and behind furniture. Creates mess with droppings and can contaminate food surfaces.

Gecko (Tarentola mauritanica)

Medium-sized gecko with warty skin texture. Commonly found on exterior and interior walls. Known for territorial behavior and loud vocalizations, especially during breeding season.

Indian Garden Lizard (Calotes versicolor)

Large colorful lizard that changes color from brown to bright orange-red. Enters homes through open doors/windows. Can bite when cornered and leaves large droppings.

Fan-throated Lizard (Sitana species)

Small to medium lizards with distinctive throat fans in males. Often enter ground-floor rooms and balconies. Create problems by hiding in stored items and furniture.

Anatomy and Physiology

Lizards exhibit a diverse range of anatomical and physiological traits that have evolved to suit their various ecological niches. These adaptations include unique sensory organs, thermoregulation behaviors, and reproductive strategies.

Sensory Organs

Lizards possess a variety of sensory adaptations that aid in their survival. Notably, many lizards exhibit small integumentary sensory organs distributed across their head and body. These organs are not only mechanosensory but also show combined sensitivity to mechanical, thermal, and pH stimuli, enhancing their ability to interact with the environment. Additionally, the pineal or “third eye” found in some species may be mistaken for a scale defect or injury, providing further sensory capabilities that assist in thermoregulation and circadian rhythms

Thermoregulation

Lizards employ a range of behaviors to regulate their body temperature, which is critical for maintaining metabolic processes. For instance, they often bask in the sun, sometimes exposing only their heads to increase heat absorption while minimizing exposure to overheating. This behavior is enhanced by the darkening of their skin through melanin dispersal, which can be misinterpreted as signs of illness or trauma. Some species, like a lacertid lizard from the Namib Desert, have evolved the ability to raise and lower their limbs to prevent overheating, a behavior that can also be mistaken for injury or pain

Defensive Mechanisms

Defensive strategies are also a significant aspect of lizard anatomy and physiology. Tail autonomy, where lizards shed their tails when threatened, serves to distract predators and facilitate escape. This behavior is widespread among lizard species, except for some families such as Agamidae and Varanidae. Following tail loss, the detached tail continues to wiggle, increasing the likelihood of the lizard’s escape.

Reproductive Behavior

Lizard courtship displays often involve visual signals to attract mates or intimidate rivals. Males may engage in behaviors such as body posturing, push-ups, and displaying brightly colored dewlaps. These visual signals are complemented by hormonal changes that affect body color and size during the breeding season. The female prairie skink, for example, maintains the humidity of her eggs through respiratory water loss, demonstrating parental care behaviors that are uncommon among lizards

Incubation and Brooding

Egg brooding, particularly in pythons, involves a unique physiological response where the female coils around her eggs and generates heat through rhythmic muscular contractions. This behavior is energetically costly but crucial for the rapid development of eggs in cooler climates.

Habitat and Distribution

Lizards exhibit a remarkable diversity in habitat preferences and geographical distribution, being classified into various families, genera, and species based on their morphological characteristics and ecological niches.

Historically, species like Belding’s orange-throated whiptail have thrived in a wide range of environments, including coastal sage scrub, chaparral, and desert regions. However, urban development and agriculture have led to extensive habitat fragmentation and loss, restricting this species to approximately 25% of its original range.

The whiptail has found refuge in protected areas like Cabrillo National Monument, which supports healthy populations due to habitat conservation efforts and reduced human disturbances.

Most lizard species are terrestrial, but some have specialized habitats, such as rock-dwelling species like Chuckwallas and arboreal types like the Green Iguana.

Urban environments have been shown to impact lizard behavior and physiology, with studies indicating that lizards in urban areas perch higher compared to those in forested environments. This behavioral adaptation may be influenced by the warmer microclimates typical of urban settings, which can affect not only perch height but also overall body condition.

The increasing urbanization of habitats poses significant challenges for many lizard species. Urban environments are often characterized by fragmented food resources, proximity to humans, pollutants, and altered microclimates, leading to a loss of biodiversity.

As such, species must adapt rapidly to survive in these modified landscapes. Research on the Cuban endemic lizard Anolis homolechis demonstrates that even non-invasive species exhibit different behaviors in urban versus forested environments, highlighting the necessity of understanding these ecological dynamics for effective conservation strategies.

In terms of ecological roles, lizards play essential parts in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, acting as predators and prey. Their adaptability to various habitats is crucial for energy transfer within these systems, indicating their importance in maintaining ecological balance.

Conservation efforts should thus consider not only habitat preservation but also the adaptive capacities of lizard populations in response to environmental changes.

Behavior

Lizards exhibit a diverse array of behaviors that are crucial for their survival and reproduction. These behaviors can be broadly categorized into defensive displays, social interactions, reproductive behaviors, and communication methods.

Defensive Behaviors

Many lizard species possess various defensive adaptations to deter predators. One common strategy is to increase their perceived size through physical displays, such as puffing up their bodies by inflating their lungs. This is often accompanied by a loud hissing sound, which can serve to intimidate attackers. The pine snake, for instance, has a specialized glottal keel that amplifies this hissing sound, enhancing its effectiveness as a deterrent. In addition to vocal displays, some lizards employ passive defensive behaviors, such as remaining motionless to avoid detection. This can involve adopting a rigid posture, mimicking the environment to blend in with their surroundings. For instance, hognose snakes are known to play dead when threatened, a behavior that can confuse or deter potential predators

Social Interactions

Lizard social behaviors primarily revolve around mating and territoriality. Males often engage in displays of dominance to attract females and defend their territory from rival males. This includes behaviors like head bobbing, which is more frequently exhibited by males, and may vary in speed and intensity depending on the context

. Territorial disputes can escalate to more aggressive actions, including chasing and biting. The social structure of lizards also allows for some species to aggregate in groups, which enhances vigilance against predators. This is particularly beneficial for juvenile lizards, as group living can reduce the risk of predation through increased observation and distraction strategies

Reproductive Behavior

Reproductive behaviors in lizards vary significantly among species. Mating rituals often involve elaborate courtship displays, including tactile interactions, vocalizations, and physical posturing. For instance, male turtles will often engage in head-bobbing and may even bite the female to immobilize her during mating

. In squamates (lizards and snakes), successful reproduction typically requires the male to position himself correctly to achieve intromission, with variations observed in the mating mechanics across different species. Such courtship behaviors can sometimes be mistaken for aggressive encounters by observers

Communication Methods

Lizards utilize a range of communication methods to convey messages to one another. While visual signals like body posturing and color changes are common, acoustic communication is also significant, particularly in larger species that can produce hissing sounds as part of threat displays. Geckos, in particular, are known for their complex vocalizations, which they use for courtship, territory defense, and distress calls. Tactile communication is another important aspect of lizard behavior, where individuals may rub against one another to establish social connections, whether in courtship or during aggressive interactions. Some chameleon species utilize substrate vibrations for communication, showcasing the diversity of methods employed by lizards to interact with each other

Conservation Status

Lizards, like many other species, face significant threats in today’s rapidly changing environment. A study by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) indicates that approximately 20% of reptile species, including lizards, are threatened with extinction due to various anthropogenic pressures. The leading factors contributing to this decline include habitat loss, climate change, pollution, and illegal wildlife trade.

Conservation Efforts

Various conservation strategies are being implemented to address these challenges. Protected areas, such as New Zealand’s predator-free islands and Southeast Asian rainforest reserves, are vital for safeguarding critical lizard habitats

. Captive breeding programs, habitat restoration projects, and community education campaigns have proven effective in promoting lizard conservation. For instance, Argentina’s Liolaemus lizard conservation project integrates habitat restoration with community engagement, demonstrating the success of holistic approaches

Habitat Loss

Habitat destruction is one of the most pressing issues affecting lizard populations. Deforestation in regions such as the Amazon significantly impacts the diverse lizard species that rely on these ecosystems for survival

. Urban development, agriculture, and other human activities have led to habitat fragmentation, which restricts lizards’ ability to find food, mates, and shelter. For example, Belding’s orange-throated whiptail has seen its range reduced to about 25% of its original territory due to extensive habitat loss, although it has found refuge in protected areas like Cabrillo National Monument

Climate Change

Climate change poses a severe challenge to lizard populations by altering their habitats and disrupting breeding cycles and food availability. Some lizard species are capable of rapid evolutionary changes, which could help them adapt to warmer environments, as evidenced by studies on brown anole lizards that suggest certain populations possess individuals with traits allowing them to thrive in extreme conditions

. However, not all species have this adaptability, and those lacking such traits may face extinction.

Pollution and Pesticide Use

Pollution also threatens lizard populations. The accumulation of pesticides in lizard tissues can pose risks to wildlife and human food chains, particularly when these lizards are consumed by predators. Sustainable agriculture initiatives aimed at reducing pesticide use in lizard-rich areas have shown promise in fostering healthier ecosystems and boosting native lizard populations

Invasive Species and Illegal Trade

The introduction of invasive species further complicates lizard conservation. Invasive lizards can disrupt native ecosystems by outcompeting local species and altering food chains, thereby contributing to declines in native populations. Additionally, the illegal wildlife trade poses a significant risk, as many lizards are captured and sold as exotic pets, leading to further population pressures in their native habitats.

Cultural Significance

Lizards hold a prominent place in the cultural traditions and mythologies of various societies around the world, symbolizing qualities such as wisdom, adaptability, and regeneration. In ancient Egypt, lizards were viewed as symbols of good fortune, while in Native American cultures, they represented survival and resilience in harsh environments. The god Sobek, depicted with the head of a crocodile, exemplifies the reverence for reptiles, as he embodied the fertility of the Nile, further underscoring the cultural importance of lizards in ancient civilizations. Asian cultures have long regarded lizards as protectors against misfortune, attributing their remarkable regenerative abilities to powers of renewal and growth. This symbolism extends to Australian Aboriginal myths, where lizards are often portrayed as tricksters or fire-bringers, reflecting the multifaceted nature of their representation in folklore. European traditions also contribute to this tapestry, with lizards appearing as omens of good fortune, highlighting their significant role in the collective imagination of diverse cultures. In addition to their symbolic meanings, lizards have been integrated into human culture as biological resources. Historically, many societies have harvested lizards for food, providing vital protein in regions where meat sources were scarce. Larger species, in particular, have been utilized in traditional medicine systems globally, with beliefs surrounding their medicinal properties, despite limited scientific backing. Lizards are not only prevalent in folklore but also in modern pop culture. They have inspired characters such as Godzilla, representing humanity’s complex relationship with nature and the immense power embodied by these reptiles. In cartoons and video games, lizards frequently appear as wise companions or formidable adversaries, echoing their ancient symbolism of wisdom and adaptability in contemporary storytelling

Cockroach Control and Management

Controlling cockroaches is a multifaceted challenge due to their resilient nature and adaptability to various environments. Traditional methods, such as over-the-counter sprays, may often fall short against these pests, especially as many cockroach populations develop resistance to common insecticides. Therefore, effective cockroach management involves a comprehensive approach that combines chemical treatments with preventive measures.

Preventive Measures

Effective cockroach control necessitates more than extermination; it requires a holistic strategy. Preventive measures play a crucial role in minimizing the risk of infestation.

- Proper food storage, using airtight containers to prevent access.

- Regular cleaning to eliminate food residues and potential hiding spots.

- Sealing entry points to reduce access to indoor environments.

- Public education on cockroach biology and behavior to empower residents and business owners to take proactive steps

Community Involvement

In multi-family units, collaboration among residents, management staff, and pest control companies is vital for effective cockroach management. Residents are encouraged to maintain sanitary conditions, report infestations, and regularly clean their spaces. Management staff should address maintenance issues, such as fixing water leaks, which can provide essential resources for cockroaches. By eliminating food, water, and hiding places, infestations can be significantly reduced.

Monitoring and Identification

Monitoring the presence and distribution of cockroaches is the first step in any management program. Visual inspections are a straightforward method to identify potential infestations. Key areas for inspection include kitchens, bathrooms, and locations near food and water sources, using a flashlight to aid in the search. For more thorough monitoring, several tools can be employed:

- Jar traps: A simple method involving a baby food jar with a greased upper portion to trap cockroaches attracted to bait placed inside.

- Glue board traps: Strategically placed in areas where cockroaches are likely to frequent, such as kitchen cabinets and near garbage cans, these traps help assess infestation levels.

Integrated Pest Management

An Integrated Pest Management (IPM) approach is recommended to effectively manage cockroach populations.

- Sealing gaps in plumbing and structural elements.

- Reducing ambient moisture through improved ventilation and drainage.

- Conducting routine inspections and applying treatments as necessar

- . Furthermore, educating residents on proper sanitation practices is essential for interrupting the cockroach lifecycle and aiding in do-it-yourself control efforts

Chemical Control Methods

Chemical treatments may include traditional insecticides and Insect Growth Regulators (IGRs), which disrupt the growth and reproductive cycles of cockroaches. Unlike conventional insecticides, IGRs prevent pests from reaching maturity and thereby reduce population growth over time

Interaction with Humans

Rats have increasingly become popular as pets due to their social nature and intelligence. Unlike the common perception of rats as pests, domesticated rats can form strong bonds with their human caregivers. Proper husbandry is critical to ensure the health and happiness of pet rats, as many basic care needs are often overlooked, leading to diseases and suffering among these animals

Social Behavior

Rats are inherently social creatures that thrive in the company of others. They exhibit complex social interactions, including grooming, play fighting, and establishing a hierarchy within their group

. Rats are known to bond closely with their human owners as well, showing affection through behaviors such as licking and cuddling. They communicate their feelings through body language, vocalizations, and even subtle gestures. For instance, rats may “brux” (grind their teeth) when they are content or huddle together to indicate a sense of safety

Impact of Human Interaction

The quality of interaction between humans and rats plays a significant role in their overall well-being. Positive experiences and regular handling can help reduce stress levels and encourage the development of trust between rats and their owners Rats that experience social stress during their formative years may show behavioral issues later, affecting their relationships with both humans and other rats

10% Discount: Applied automatically for first-time bookings.

Conservation Status

Rats play a significant role in various ecosystems and exhibit a diverse range of species, some of which face significant threats to their survival. The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has categorized numerous rat species on its Red List of Threatened Species, primarily due to habitat loss and declining populations. Out of the species assessed, several are classified into varying levels of concern.

Threatened Species

As of recent assessments, there are 16 rat species that are considered threatened with extinction.

Near Threatened

- Rattus elaphinus (Sula Archipelago rat)

- Rattus feliceus (Spiny Seram Island rat)

- Rattus jobiensis (Yapen rat)

Vulnerable

- Rattus hoogerwerfi (Hoogerwerf’s Sumatran rat)

- Rattus palmarum (Zelebor’s Nicobar rat)

- Rattus richardsoni (Glacier rat)

- Rattus satarae (Sahyadris forest rat)

- Rattus stoicus (Andaman rat)

- Rattus xanthurus (Northeastern Xanthurus rat)

Endangered

- Rattus burrus (Miller’s Nicobar rat)

- Rattus hainaldi (Hainald’s Flores Island rat)

- Rattus lugens (Mentawai Archipelago rat)

- Rattus montanus (Sri Lankan mountain rat)

- Rattus ranjiniae (Ranjini’s field rat)

- Rattus simalurensis (Simalur Archipelago rat)

- Rattus vandeuseni (Van Deusen’s rat) .

Ecological Importance and Risks

Rats are an integral part of their ecosystems, serving as both predators and prey. They contribute to nutrient cycling and seed dispersal. However, when habitats are disturbed, their populations can surge, leading to ecological imbalance. In many regions, particularly in urban areas, rats are often viewed as pests due to their potential to spread diseases and damage infrastructure

Conservation Challenges

Despite the ecological significance of rats, many species remain vulnerable. Habitat destruction due to urban development, agriculture, and climate change are major threats that lead to declining rat populations. Furthermore, competition with introduced species like the brown and black rats often exacerbates the situation for native rat populations, pushing them closer to the brink of extinction . Thus, concerted conservation efforts are essential to mitigate these threats and preserve the diversity of rat species across different habitats.

Cultural Significance

Rats have held a significant place in various cultures and mythologies throughout history. Their roles range from symbols of pestilence to emblems of intelligence and resilience, reflecting the diverse perspectives societies hold about these creatures.

Folklore and Literature

One of the most enduring tales associated with rats is “The Pied Piper of Hamelin.” This story, originating in Germany around the late 13th century, tells of a rat-catcher who uses enchanted music to lead away a rat infestation. When the townspeople refuse to pay him, he exacts revenge by luring away their children. This tale has inspired countless adaptations in film, theater, and literature, including works like Terry Pratchett’s The Amazing Maurice and his Educated Rodents and the Belgian graphic novel Le Bal du Rat Mort.

. The narrative has also been linked to historical events, such as the Black Plague, which was exacerbated by the presence of black rats in urban areas.

Symbolism in Society

In various cultures, rats embody contrasting themes. In some contexts, they are seen as harbingers of disease and misfortune, symbolizing filth and decay. Conversely, in others, they represent survival, adaptability, and cleverness. This duality can be seen in their representation in popular media. For instance, Pixar’s Ratatouille features a rat as the protagonist, portraying him as resourceful and aspirational, challenging negative stereotypes associated with his species

Scientific and Cultural Studies

The cultural significance of rats has also attracted scholarly attention. Research has explored their representation in art and literature, revealing how these animals have been used to reflect societal fears and aspirations. Additionally, studies have examined the psychological implications of human-rat interactions, emphasizing the complex relationships humans have with these animals, from laboratory settings to urban environments

Rats in Popular Media

Rats have become prominent characters in various forms of entertainment. Notable examples include Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH, where they are depicted as intelligent beings with their own society, and Rizzo the Rat from The Muppets, who adds a comedic touch to the rodent’s public persona